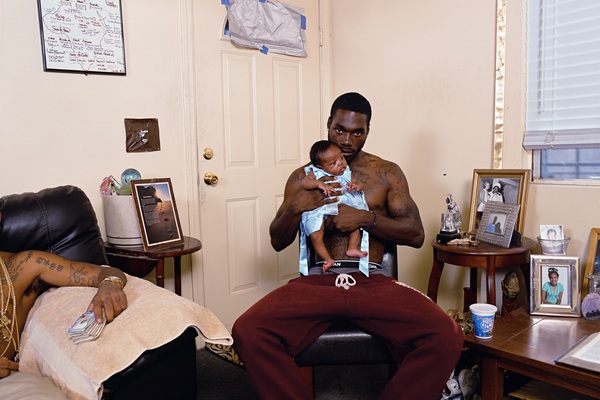

Image: Deana Lawson, Sons of Cush, 2016 © Deana Lawson.

Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, and Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago.

The Barbican’s new exhibition, Masculinities: Liberation through Photography considers how masculinity has been assigned, performed and socially constructed as expressed and documented from the 1960s to the present day.

By outlining the often complex and sometimes contradictory representations of masculinities, the exhibition draws attention to how negative stigma and representations of masculinity prevent people from fully embracing their vulnerabilities and lived experiences.

Barbican Curatorial Assistant, Chris Bayley spoke to Respect, breaking down his views on the social expectations of masculinity and how society can benefit from understanding and accepting plural masculinities.

“In context with Respect and the ways in which the charity supports individuals, I think, in many ways, men are being asked to live up to ideals that hinder their personal emancipation,” Chris said.

For those that feel constrained by the pressures of living up to narrow definitions of masculinity and gender, Chris believes that by challenging these definitions, it may become easier for men to confront complex issues, such as suicide and mental health, as well as domestic abuse for male perpetrators and male victims.

“It’s important to start thinking about our own identities, because as soon as you start breaking them down, you can see yourself,” Chris said. “When men are being asked to live up to ideals or stereotypes of traditional masculinity, those expectations can be incredibly damaging.”

These stereotypes exclude and erase many identities, with members of marginalised masculinities being particularly outcasted.

Looking at Marginalised Masculinities

How do stereotypes play into understandings of masculinity? How do they impact your perceptions of Black men, other people of colour, disabled and LGBTQ+ men, and men with other protected characteristics?

Chris explains that, in order to directly approach the social barriers surrounding masculinity and gender, we must engage in separate conversations about multiple marginalised masculinities. He explains that the show and wider Barbican programme wanst to look beyond Western-centric art history and white, cisgender male viewpoints.

“Those who do not sit within this dominant heterosexual masculinity, for example women, people of colour, lower class, non-able, disabled and queer bodies are almost denied their masculinity – they’re outcasted as the ‘other’,” Chris said.

One of the chapters in the exhibit, Reclaiming the Black Body, shows the black male experience through the work of artists who have been consciously rejecting expectations of race, gender and the white gaze over the last five decades, by reclaiming the power to fashion their own identities.

“The mainstream representation of black masculinity was born out of a violent history of slavery and prejudice, which still persists today,” Chris said.

Social expectations of masculinity and fatherhood may leave men feeling alienated from caregiver roles. Black men face additional stigma in fatherhood due to racial stereotypes. In Deana Lawson’s, Sons of Cush, she actively confronts stereotypical representations of Black families and challenges the myth of “the absent father.”

The exhibition also attempts to draw viewers into discussions of disabled and queer masculinity by highlighting artists who have created what Chris describes as a ‘politically charged queer aesthetic’, rejecting the patriarchal heterosexual system they’ve been pressured to fit into.

Reflecting inwards

We need to examine what we’ve been taught and why we believe men must live up to these ideals. When Chris first began putting together this exhibition with Alona Pardo, the exhibition curator, he didn’t really think about his own ideas of masculinity, but the deeper he dug, the more he began to question it.

“The show wasn't about setting out to answer what masculinity is,” Chris said. “For me, gender is a social construct, and gender and sex are not synonymous. Gender is learned, taught and performed. When we begin to really scrutinise and unlearn things, we can look at the plurality of masculinity and gender more widely.”

Conversations about identity may seem difficult to start, but by opening these talks and reviewing positive and negative expectations, we can better understand how they impact our well-being.

Check out Masculinities: Liberation through Photography and book your ticket now.

The Barbican has offered Respect’s members special access to the online Community View of their exhibit, Masculinities: Liberation through Photography.

Quoted content does not necessarily represent Respect and our views.